George Snowball and his grocer's shop

Enter a grocer's shop in the eighteenth century through the collection of a famous shop keeper.

Let me introduce you to George Snowball in his grocer’s shop, just off the Strand in London in the early eighteenth century. As you enter you smell waxed wood, fragrant tea and pungent coffee. There are boxes and canisters, cabinets and drawers and your eyes have to adjust the gloom inside.

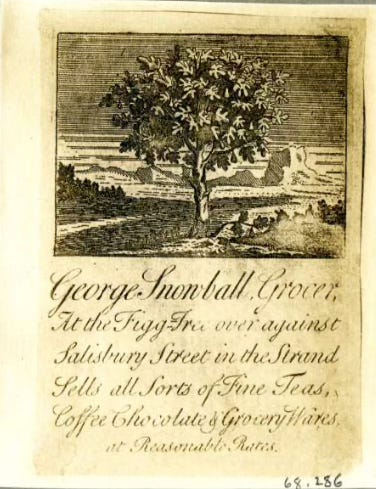

Hanging outside his shop is likely a street sign bearing a Fig tree, an emblem of this trade. It would have creaked and dripped in the wind and rain.

The only reason I can magic up George for you today is that his trade card has survived.

But how did it survive? And what is a trade card anyway?

Let me first give you an example. George Snowball’s card.

Trade cards can be likened to those business cards people used to collect. I confess I had a Filofax in the 1980s with pockets to store them in. But unlike modern business cards, eighteenth-century trade cards are most often on paper, and they act as advertisements.

They are engraved and printed announcements of shopkeeper’s wares, where they are to be found, the name of the tradesman, the sign of his shop or the number of his street.

They often survived because collectors thought trade cards were valuable and bequeathed their collections to a museum collection

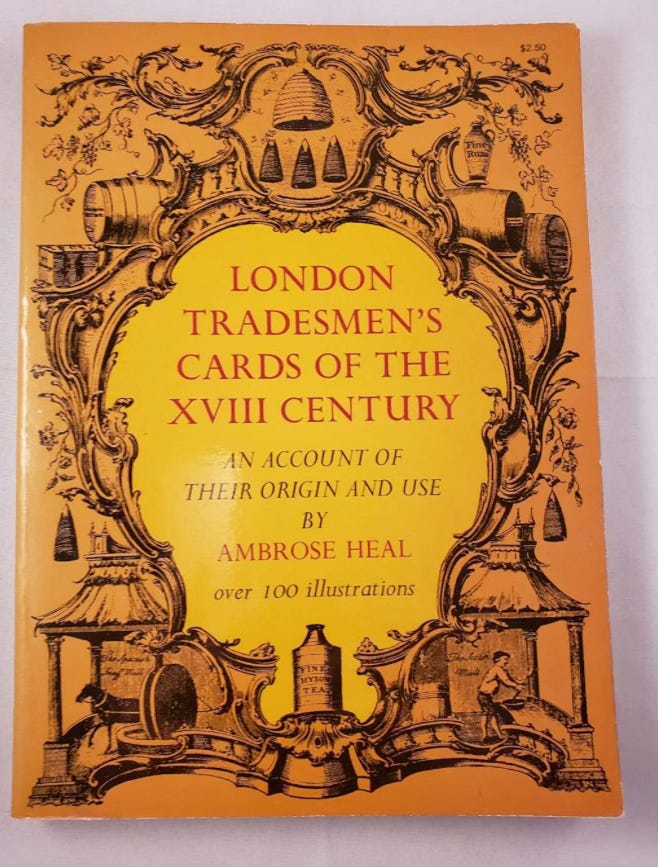

Let me introduce you to the collector who found George Snowball’s trade card (and many, many more) Ambrose Heal. Another shopkeeper of sorts.

Sir Ambrose Heal (1872-1959) joined the family firm, Heal & Son, in 1893. He designed simple, successful furniture for the store, so simple that some staff called it prison furniture. In 1913 he became the chairman and transformed the Tottenham Court Road shop making it profitable. Heal’s is still in the UK a household name.

But importantly for us, while doing all of this, he collected trade cards from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and wrote about his collection in this book (below) published in 1925.

Trade cards, Heal tells us, are a source of archaeological interest. They are common workaday items with a simple purpose, to tell people what a business does and act as a promotional item. But more than that, he implores:

‘[their] value as a record is so true, and…gives it a touch of vitality that many volumes of historical research do not possess’

His collection was bequeathed to the British Museum on his death.

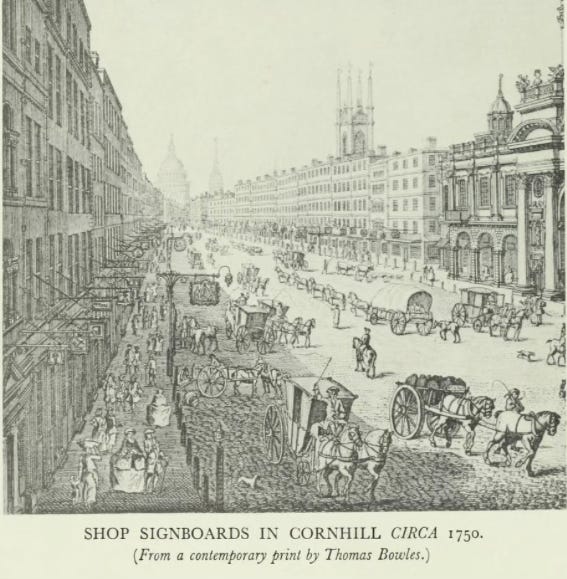

But other cards in his collection hold a second meaning. They can tell us how streets looked in the Georgian era.

Look below at Cornhill around 1750 in this print by Thomas Bowles and feast your eyes upon all the shop signboards.

Heal tells us that few of these old shop signboards have survived. There are a few examples in museum collections and a few examples still to be seen in England.

Heal, writing in the late 1940s,

‘Now and again in a country town, one will still see hanging out over shops simple objects…such as the coiled tobacco roll, the barber’s pole, a padlock or a kettle at ironmongers or a large red hat over the hatters.’

You may have seen the occasional shop signboard like that.

But Heal showed how old signboards were recorded on trade cards.

Let me give you an example of the Sign of the Frying Pan that used to hang proudly on the corner of Frith Street and Compton Street in London’s Soho.

The purpose of signboards was to identify a business when few people were able to read a shopkeeper’s name.

From records of the 1600s we know that identifying a shop with a signboard was common. After the rebuilding of the City after the Great Fire of 1666 stone panels started taking off but the majority still wanted a signboard either on a post or hanging on an iron bracket. And the signs got bigger and bigger.

They got so big that in 1718 an enormous sign in Bride Lane fell and brought the front of the house down, killing four people. Calls for safety were raised but it wasn’t until 1761 that the City of London ordered the removal of hanging signs. House numbering came in shortly afterwards though it wasn’t until about 1770 that three-fourths of the houses had numbers.

That creaking olive tree signboard outside the plain grocery shop of George Snowball was likely removed too. If only it had ended up in a museum collection.

But we can imagine it, and him, through the trade card he left behind and was collected by Ambrose Heath.

In his words:

‘In their way, they have a touch of romance…the plain tale of the shopkeeper, proud enough of his trade and his distinctive device to have his advertisement sheets well designed, beautifully lettered and finely engraved’.

Lovely time travel to start the week.

My 3x great grandfather was a bookbinder in Clerkenwell. I wonder if he had a tradecard